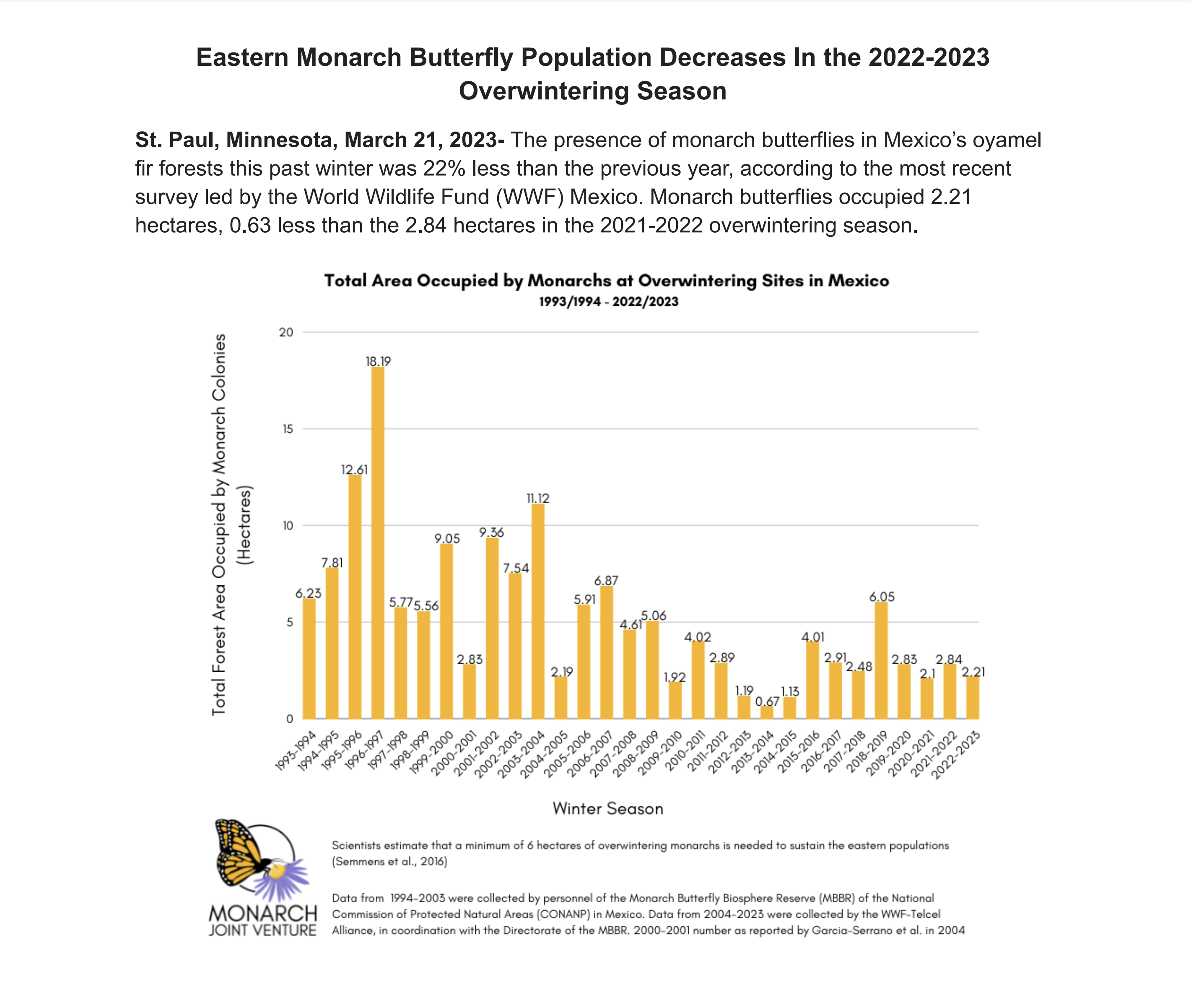

The presence of the Eastern Monarch population in Mexico’s transvolcanic mountain forests was 22 percent less this winter compared to last winter, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) annual count.

Rather than counting individual butterflies, the Monarchs are counted by the number of hectares they occupy. This past winter, the Monarchs occupied 2.21 hectares, down from 2.84 hectares in 2021-2022. A hectare is approximately 2.47 acres. A threshold of at least 6 hectares is recommended to sustain the eastern population.

For more precise information on how the Monarchs are counted read more from Monarch Joint Venture –

Estimating the Number of Overwintering Monarchs in Mexico

Contributors: Gail Morris, Karen Oberhauser, Lincoln Brower

Every year we anxiously await news of the monarch overwintering population count from Mexico. When are they done and how are the monarchs counted?

Monarchs go through four phases while overwintering in Mexico: their arrival, the establishment of an overwintering colony, colony movement and finally the spring dispersal.

The first fall migrating monarchs usually arrive at the overwintering sites in late October through mid-November. In this early phase, the monarchs are largely scattered and diffuse in their flight, moving frequently through an area and eventually creating small clusters at night, while still continuing to move through the forest. During the day, their movement is common and widespread, as they search for the perfect sheltered location to spend the winter.

As temperatures dip colder, monarchs begin to form larger and denser clusters, settling into smaller and protected areas at elevations of 2900-3300 meters (9,500 to 10,800 feet.) This usually occurs from mid-December through early February and the monarchs principally roost in oyamel trees although they use pines and other trees as well. This is the coldest time of the year where monarchs are most compact and stationary in their clusters, a time of winter survival with little movement.

By mid-February, temperatures are gradually climbing and the monarchs begin expanding their clusters. They slowly begin to move down the mountain on warm, sunny days searching for water to drink in nearby creeks. They return to the safety of the nearby forest as temperatures drop. The final phase is the monarch dispersal as the population gradually begins its movement north.

The traditional time of the annual overwintering count in Mexico is in late December when the clusters are most compact and movement is minimal. So how are the estimates done? How do you estimate how many monarchs there are in an area?

The World Wildlife Fund and the MBBR have measured the monarch population each year since the winter of 2004-2005. The occupied trees are mapped in each colony. Beginning with the highest tree in the periphery, the counters use a measuring tape or distance meter and compass to measure the perimeter using a series of lines connecting trees along the boundary. The enclosed area is then calculated in hectares.

Researchers have estimated that there are approximately 21.1 million butterflies per hectare, although this number most certainly varies with the time of the winter as the colonies contract, expand, and move. It also varies with the density and size of the trees in the colony. Based on this estimate the largest population of monarchs occurred in 1996-1997 when the colonies covered over 18 hectares and contained an estimated 380 million butterflies. To date the lowest population recorded was in 2013-2014 with 0.67 hectares and approximately 14 million monarchs.

While population estimates are recorded back to the winter of 1976-1977, long term counts of monarchs previously occupying the overwintering sites for comparison are limited due to a lack of complete data.

Keep in mind that the monarch overwintering estimates in Mexico are done when the monarchs are most compact in the trees. While counts continue biweekly during the time the monarchs are in the area, the end of December counts are used for comparison from year to year.