In February of 2014 when I traveled to El Rosario Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve in Angangueo to film the Monarchs, we encountered some difficulty locating the butterflies. Because of global warming conditions the Monarchs had roosted much further up the mountain than was typical. We needed to climb an additional 1500 feet, nearly to the top of the mountain. There was no place higher for the butterflies on this mountain and I wondered at the time, where would they go as the earth becomes increasingly warmer.

In February of 2014 when I traveled to El Rosario Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve in Angangueo to film the Monarchs, we encountered some difficulty locating the butterflies. Because of global warming conditions the Monarchs had roosted much further up the mountain than was typical. We needed to climb an additional 1500 feet, nearly to the top of the mountain. There was no place higher for the butterflies on this mountain and I wondered at the time, where would they go as the earth becomes increasingly warmer.

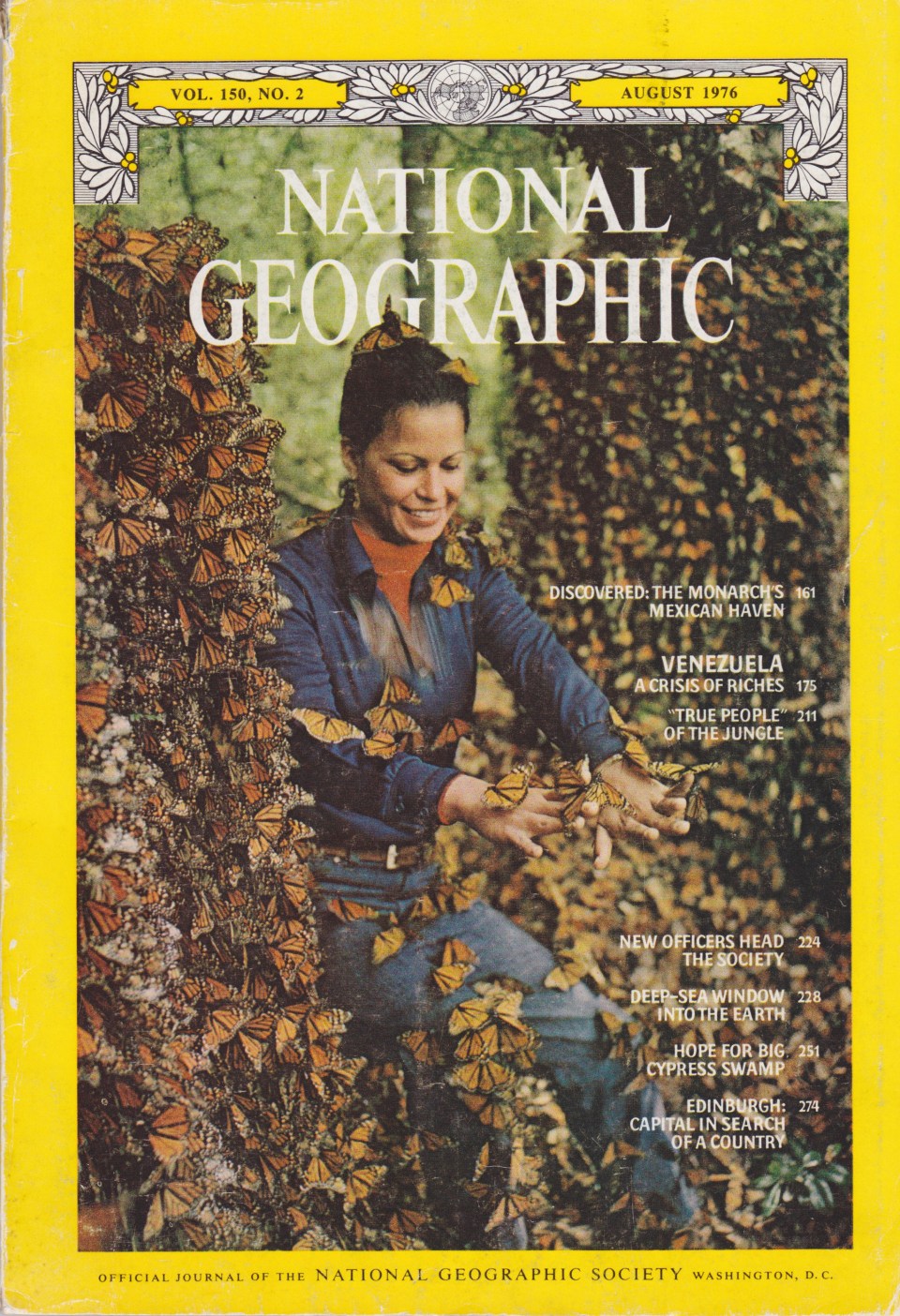

Butterflies are heliothermic, which means they gain heat from the sun. During the winter it is imperative that the butterflies remain relatively cool and in a state of sexual immaturity, called diapause. The sheltering boughs of the sacred Oyamel Fir (Abeis religiosa) trees and the cool temperatures at the higher altitudes of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Mountain Belt, in the past, have provided optimal habitat for the butterflies.

Leaving the Chaparral and Entering the Oyamel Fir Forest

Leaving the Chaparral and Entering the Oyamel Fir Forest

Oyamel Fir Forest

Oyamel Fir Forest

The butterflies currently roost at altitudes between 9,500 and 10,800 feet. Mexican scientists are planning to progressively move the trees higher up the mountainsides in a race to save the fir trees. Last summer several hundred seedlings were planted at 11,286 feet where habitat best suited to Monarchs is expected to be by 2030.

Excerpt from “To Protect Monarch Butterfly, a Plan to Save the Sacred Firs”

By Janet Marinelli

“While U.S. biologists urge gardeners to plant milkweeds to help restore the monarchs’ summer habitat, Mexican scientists are pinning their hopes on a plan to move the species progressively higher up local mountainsides in a race to save these firs and the butterflies that depend on them. “We have to act now,” says the plan’s architect, Cuauhtémoc Sáenz-Romero, a forest geneticist at the Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo. “Later will be too late, because the trees will be dead or too weak to produce seeds in enough quantity for large reforestation programs.”

When the rainy season arrived last summer, a few hundred seedlings were planted at 11,286 feet, where habitat suited to oyamel fir trees is expected to be by 2030. By then, according to retired U.S. Forest Service geneticist Jerry Rehfeldt, who co-authored a paper with Sáenz-Romero on global warming’s effect on oyamels, temperatures in the reserve could rise above pre-industrial levels by 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit by 2030, and suitable habitat could shrink by nearly 70 percent. The scientists’ research further suggests that by the end of the century, habitat that meets the fir’s needs may no longer exist anywhere inside the reserve. Trees would have to be planted at higher altitudes on peaks more than 100 miles away from the monarch’s migratory home.

The sacred fir is a poster child for the plight of trees around the globe. Trees provide habitat for countless species and underpin ecosystems as well as human economies, but as a group they are highly imperiled. A diagram in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2014 Working Group II report shows that of all life forms, trees are least able to respond to rapid climate change. Rooted in place, they have not evolved for rapid locomotion. Many take decades to mature and reproduce.

The breakneck speed of current global warming dwarfs anything in the fossil record, even what Lee Kump, professor of geosciences at Penn State University, has called “the last great global warming” 56 million years ago during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. At that time, over the course of a few thousand years, global temperatures soared 9°F as the supercontinent Pangaea broke apart. By comparison, if carbon emissions are not slashed soon, scientists warn it’s possible we could witness that much warming in a matter of centuries, if not decades. Without human help, trees and many other plant and animal species most likely won’t be able to migrate fast enough to keep pace with rapidly changing conditions.”

READ THE COMPLETE ARTICLE HERE

So many thanks to my friend Eric Hutchins for forwarding this article!!

Oyamel Boughs Enveloped in Monarchs

Oyamel Boughs Enveloped in Monarchs

Great Spangled Fritillary nectaring from coneflower, Gloucester Harbor Walk Butterfly Gardens

Great Spangled Fritillary nectaring from coneflower, Gloucester Harbor Walk Butterfly Gardens