NRCS, USFWS Partner to Accelerate Conservation on Agricultural Lands for the Monarch Butterfly

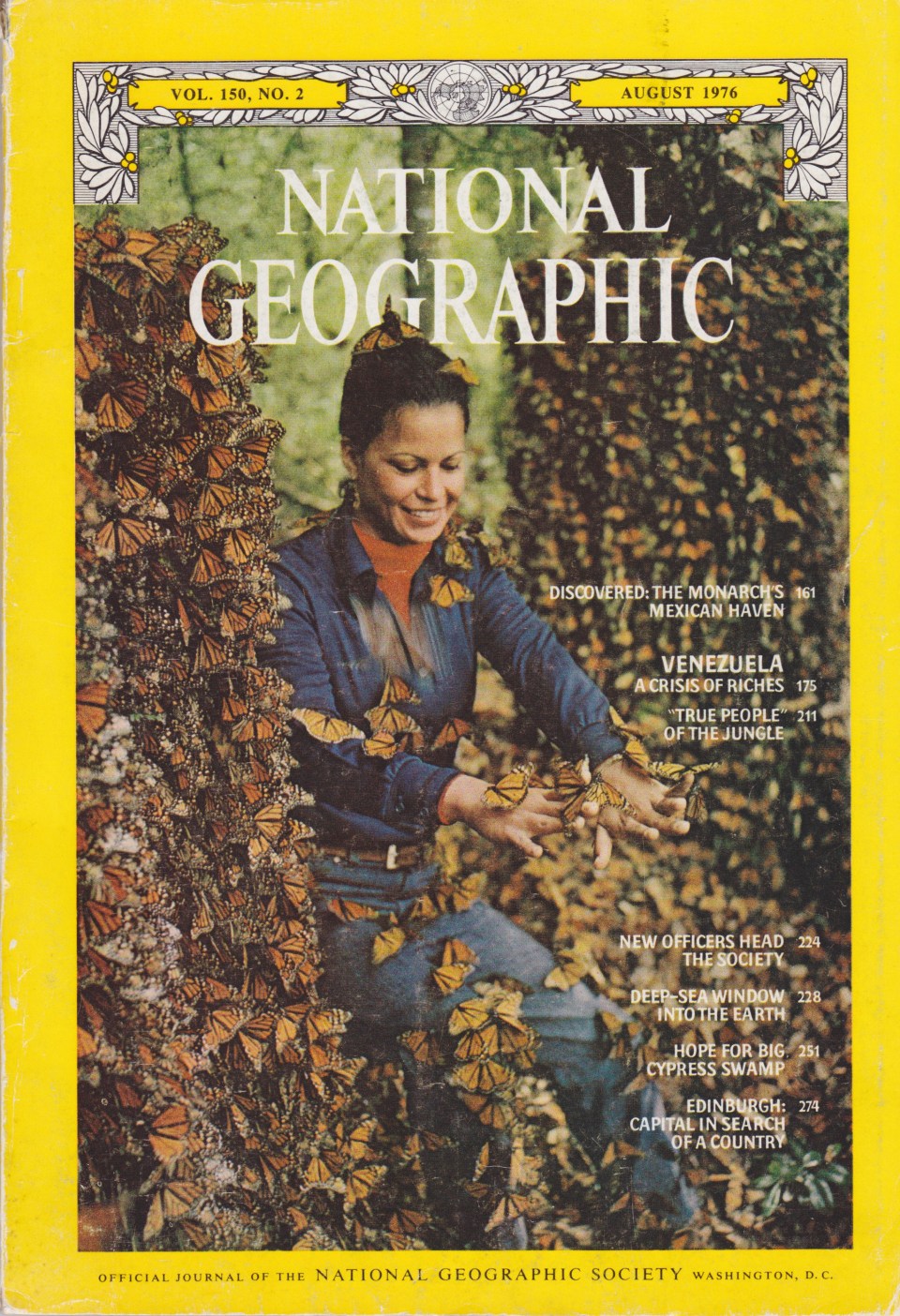

The monarch butterfly is a new national priority species of Working Lands for Wildlife (WLFW), a partnership between the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). Populations of monarchs, a pollinator species cherished across North America, have declined significantly during the past two decades. This collaboration aims to help the species recover by working with agricultural producers to make wildlife-friendly improvements on their farms, ranches and forests.

“Producers can make simple and inexpensive tweaks on working lands that provide monumental benefits to monarch butterflies and a variety of other insects and wildlife,” said NRCS Chief Jason Weller. “By adding the monarch to Working Lands for Wildlife, we can accelerate conservation for the species at the heart of its migration corridor.”

NRCS and USFWS recently completed a conference report that explains how conservation practices can help the eastern monarch population, a species known for its remarkable annual, multi-generational migration between central Mexico and the United States and Canada. This report is an initial step toward adding the monarch to WLFW, which uses a science-based, targeted approach to help a variety of at-risk species.

“We need to make every effort to help ensure monarchs don’t become endangered now and in the long term,” said USFWS Midwest Regional Director Tom Melius. “Conservation efforts on agricultural lands across the nation can have a significant positive impact on monarchs as well as many other pollinator insects and birds. Working with farmers and other private landowners, we can ensure a future filled with monarchs.”

The monarch butterfly joins an array of wildlife species across the country already part of WLFW, including the greater sage-grouse and New England cottontail, two recent successes in species conservation. The USFWS determined in 2015 that the two species didn’t warrant protections under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) because of voluntary conservation efforts underway to restore habitat.

Through WLFW, NRCS provides technical and financial assistance to help producers adopt conservation practices that benefit the monarch. Meanwhile, through the conference report, the USFWS provides producers with regulatory predictability should the monarch become listed under the ESA. Predictability provides landowners with peace of mind – no matter the legal status of a species under ESA – that they can keep their working lands working with NRCS conservation systems in place.

Work through WLFW centers on 10 states in the Midwest and southern Great Plains that are considered the core of the monarch’s migration route and breeding habitat. Much of this work will focus on planting and enhancing stands of milkweed and other high-value nectar plants for monarchs. Assistance is available to producers in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas and Wisconsin.

USFWS has committed significant funding – $20 million over five years – to support monarch conservation efforts. Additionally, USFWS is working with partners, including the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, National Wildlife Federation and the Mexican and Canadian governments to leverage resources and investments to support and implement conservation actions across the continent.

During the past two years, NRCS has made available $6 million through a variety of Farm Bill conservation programs for monarch conservation in the 10 states. Additionally, NRCS is working with partners, including The Xerces Society and General Mills, to increase staffing capacity to help producers design customized conservation strategies for working lands.

The two agencies’ efforts contribute to a multi-agency, international strategy to reverse the monarch’s population decline in North America, estimated to have decreased from one billion butterflies in 1995 down to an estimated 34 million. Through the National Strategy to Promote the Health of Honey Bees and Other Pollinators,  released by the White House, the United States has a goal of increasing the eastern population of monarchs back to 225 million by 2020.

released by the White House, the United States has a goal of increasing the eastern population of monarchs back to 225 million by 2020.

Producers interested in NRCS assistance should contact their local USDA service center to learn more. NRCS accepts landowner enrollment applications on a continuous basis. NRCS offers more than three dozen conservation practices that can provide benefits to monarchs as well as a variety of other pollinators.

released by the White House, the United States has a goal of increasing the eastern population of monarchs back to 225 million by 2020.

released by the White House, the United States has a goal of increasing the eastern population of monarchs back to 225 million by 2020.